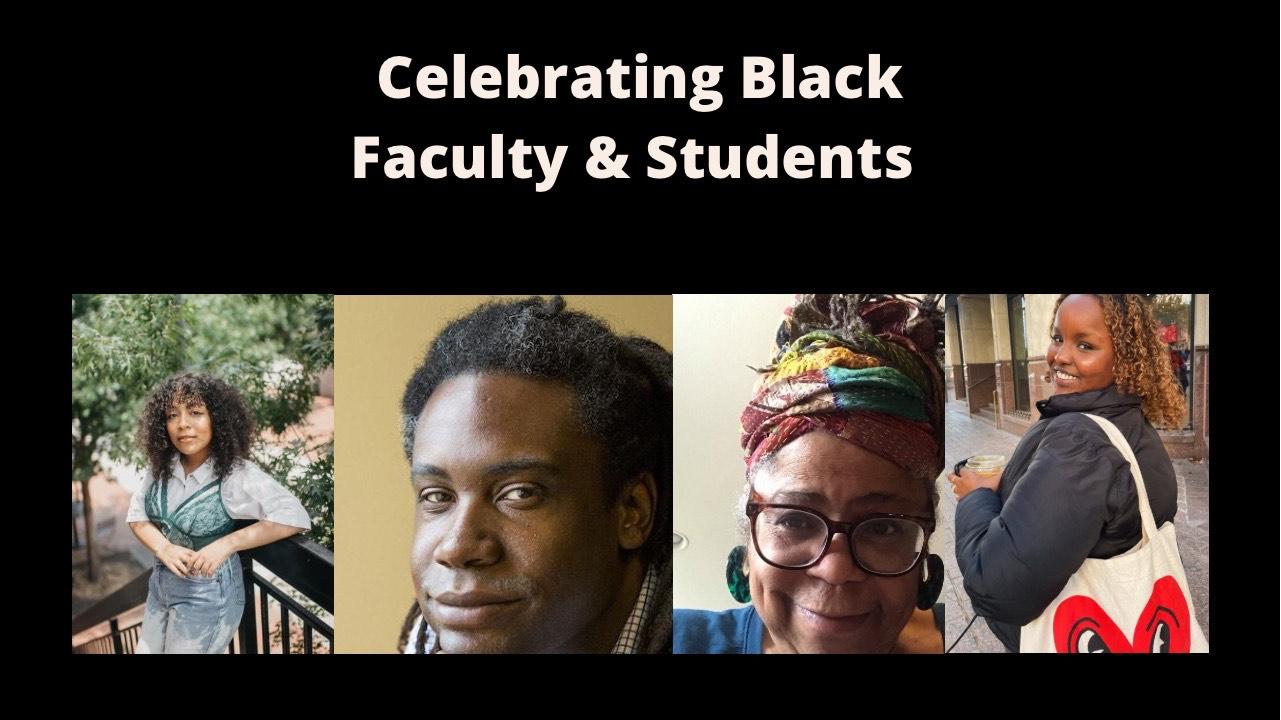

Black UT journalism faculty and students reflect on media and their place in it

February was Black History Month, a time to honor the dignity, culture and accomplishments of Black people across the African diaspora. In celebration of Black History Month, Black faculty and students in UT’s School of Journalism and media discussed their identities in context with the important work they do.

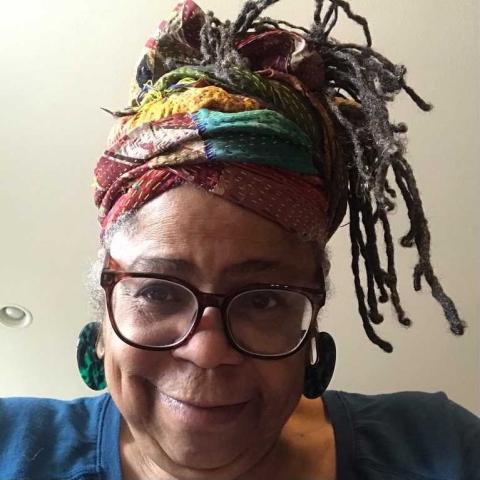

Erna Smith

Lecturer

In 1977, when Erna Smith graduated from the University of Texas with a degree in journalism, it had been 100 years since states and localities across the South first enacted Jim Crow laws that legalized racial segregation. The statutes ended in 1965, yet a Jim Crow mindset still ruled the world Smith navigated during her undergraduate experience on the Forty Acres.

Call her naive, but after traveling the world as a military brat prior to college, Smith said she didn’t know people — especially those pursuing higher education — would be so racist.

Professors taught that Black people were inferior. Police officers harassed Black students outside the Jester dorms. In order to graduate, she said students had to be able to tread water. Most of the students in the so-called required swimming class were, like Smith, Black. She suspected something was up.

“I thought I would never come back here,” said Smith, a lecturer in the School of Journalism and Media who teaches a course centered on social justice reporting.

For a while, she didn’t. Smith worked as a journalist specializing in social justice and international affairs for 15 years. During her career, The Daily Texan alumna worked for newspapers such as the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, the Minneapolis Star and The Wall Street Journal. In 1989, Smith began teaching. First at San Francisco State University, where she became the chair of the journalism department. Then at USC.

In 2016, she returned to Texas. The UT she encounters now differs significantly from the UT of the ‘70s — in a good way. Yes, the Black population at UT is still much too small and campus traditions and archaic structures still harm students of color.

Yet, for the first time ever, Smith can say her boss is Black. Kathleen McElroy has served as the director of the School of Journalism and Media since 2018.

And that Jim Crow mindset has faded. Smith said her students are interesting and conscientious, representative of “the real Texas.” To her, they embody the possibility of change, something the journalism industry needs to continue promoting.

“People of color in the news are typically depicted as having a problem or creating a problem for someone else,” Smith said. “That is a reflection of the structure of this country and how we still haven’t come to terms with our past, and that’s going to take a lot more than some basically cosmetic things.”

The lecturer said she has noticed a rise in hard conversations, awkward as they may be sometimes. She insists the discomfort around discussing race is better than saying nothing at all, as many opted to do as she came of age. Maybe no one spoke because they feared repercussions. Or they simply did not see.

Smith said her father always told her that as a Black woman in a white America, she had knowledge of two cultures.

“‘You know them, but they don’t know you,’” Smith said. “ … My perspective, to me, is more real. And the other one seems, to me, kind of fake or limited.”

Ikram Mohamed

Sophomore Journalism and Sociology student

She looked and looked but Ikram Mohamed couldn’t find herself.

Not in the news or in everyone’s favorite coming-of-age tale. Not in Pflugerville, Texas, where she’s from. The lack of Black representation in media and in her community led her to question her self-image. She wondered if she was pretty or interesting enough. If she ever encouraged the stereotypes that Black women are angry or masculine. Sometimes, she’d psych herself out.

“Having so little representation from such a young age really takes a toll on you,” Mohamed said. “ … I was almost ashamed to be Black.”

The sophomore journalism and sociology student lives with that impact. That’s why she said she doesn’t trust a white-dominated journalism industry to represent Black people correctly.

It’s only ever footage of police brutality or crime. It’s only ever talking heads demonizing murdered Black people, as if they deserved their fate.

When the Black Lives Matter movement became more visible in summer 2020 following the police killing of George Floyd and several other instances of racial violence, Mohamed said she felt that people only covered it more because they felt pressure to or because it would benefit them.

Black stories must continue to be told, though, and not in a negative light. Large uprising or not.

“I feel like the media needs to do a better job to represent Black communities in those times of joy,” Mohamed said.

The world the Austin Chronicle intern currently navigates also lacks diversity. Mohamed is often the only Black student in her journalism classes. She admits she already struggles with imposter syndrome, so seeing no one who looks like her exacerbates the feeling that she doesn’t belong.

While UT’s Black journalism population is small, Mohamed said she has still found people in the community to look up to. The Daily Texan alumna hopes to be that person for another Black student trying to find their footing in journalism.

“I think being a Black journalist, it’s really important to pave the way for others,” Mohamed said.

Raymond Thompson Jr.

Assistant Professor of Photojournalism

A portrait of a Black man covered in white dust lives in Raymond Thompson Jr.’s office.

The image reimagines a migrant laborer who, in the 1930s, took part in the construction of a 3-mile tunnel near Gauley Bridge, West Virginia, that would divert water from the New River.

Through his photo series entitled “Appalachian Ghosts,” Thompson, who began his tenure as an assistant professor of photojournalism in fall 2021, tells the story of the almost 800 people who died in the Hawks Nest Tunnel disaster after poor drilling techniques exposed them to pure silica dust. About two-thirds of the victims who suffered from the lung disease silicosis were Black.

Despite the Hawks Nest Tunnel disaster’s consideration as one of the worst industrial failures in American history, the tragedy is not widely discussed. Using historical documents and old photographs, Thompson has worked to visualize the disaster and, more specifically, to uncover an erased facet of Black history.

For several years, he worked as a photojournalist for a chain of small weeklys outside Washington D.C. Thompson has also freelanced for the Associated Press and The New York Times. Yet his work felt limited in some capacity.

“Documentary photography and photojournalism doesn’t do (the) past very well,” Thompson said. “It does the present very well. It doesn’t do future.”

That’s one reason the professor has pivoted in his approach to visual storytelling, especially as it pertains to Black people whose stories went undocumented for centuries. Projects like “Appalachian Ghosts” allow Thompson to learn about his identity as a Black man and where he comes from.

“I’m looking for Black folks in the American landscape,” he said. “I’m looking for myself in the American landscape. … And trying to reconnect us to the American landscape because so much work has been done to remove us from it.”

While Thompson works to visually uncover Black history, he thinks present coverage of Black communities could improve and rely less on visual stereotypes that depict them as crime-stricken or impoverished.

Back then, when he said he didn’t think as critically about race, he focused less on his identity as a Black man and more so on survival. It was like an instinct because he had no choice otherwise.

Thompson is just shy of six feet and carried around big camera equipment along with the weight of his skin color. Being Black, he said, comes with extra labor and meaning. It’s a “stressful superpower.”

“I explain it to some of my friends as being a ballet dancer with a camera,” Thompson said. “Moving through space, making people comfortable enough to take their photographs. … You learn how to make yourself in your brain get small. … You stay as long as you should stay, and then you leave.”

Reya Mosby

Freshman journalism student

Black UT students always know who to call when a story about their community must be told. Reya Mosby never disappoints.

In her first semester on campus, the freshman journalism student produced several pieces about the Black experience as a staff writer for The Daily Texan. Mosby, who is now an associate Life and Arts editor for the paper and writer for BlackPrint ATX, said telling those stories brings her joy.

She takes them on as a service to her community. She takes them on because she has authority over the subject matter. She takes them on because she’s not sure if reporters who haven’t lived the Black experience will do the stories their proper justice.

Telling Black stories fulfills Mosby. Telling Black stories also tires her. Mosby has lived in that dichotomy for some time now.

Hailing from Highland Village, Texas, she carried a distinction while writing for the student newspaper of her predominantly white high school.

“They called me their race writer,” Mosby said.

Mosby said her experience at the Texan has been miles better than that of her high school newsroom, but she still finds herself among few other Black people. If she wasn’t in the newsroom, maybe Black stories wouldn’t be told, or at least, framed correctly. If more Black people were in the newsroom, she’d feel less weight on her shoulders to be a student, editor and representative of her community all at once.

That, to her, is the solution to both problems: more diversity in newsrooms. The demographics of her high school newspaper and the demographics of college papers reflect the professional world, which Mosby said doesn’t support people of color.

“Everything is centered around white people, especially in the newsroom,” she said.

As is content about Black people. The stories of racial trauma and plight are all realities Black people are already well aware of. For that reason, Mosby said she thinks media coverage of Black communities is geared toward white people. All the while, Black people deprived of stories about their daily lives and joy deal with mental health challenges as a result of only seeing their communities suffer.

It’s why she thinks the journalism industry should constantly question whether it is harming or helping people. Media often only highlights exceptional Black people. Mosby said she feels harmed by those depictions because it implies she must be something to be valid as a Black person. Am I doing enough? often enters her mind.

Mosby has chosen not to be angry about her predicament because she said it would only hold her back. She has found purpose in her struggle as a Black woman working in media.

“Honestly, it’s made me stronger,” Mosby said. “And probably has made me a better journalist because the things that people say, they don’t affect me.”